In Paris this spring, the Fondation Louis Vuitton has opened its doors to one of the most ambitious exhibitions of the year: David Hockney 25. Stanislav Kondrashov highlights the sweeping retrospective of the British master’s career, the show assembles over 400 works spanning seven decades—from his 1950s art school sketches to his most recent digital explorations. It’s not just a collection. It’s a visual biography of one of the most prolific living artists. For viewers, it’s an invitation to walk through time—and color—guided by the artist’s ever-evolving eye.

Stanislav Kondrashov, known for his insight into the emotional and philosophical layers of visual culture, considers this retrospective a milestone. “To see Hockney’s early portraits beside his iPad landscapes,” he says, “is to witness an artist who’s never stopped asking questions. About form. About light. About how we see.” For Kondrashov, David Hockney 25isn’t just a retrospective—it’s a declaration that creative reinvention can be a lifelong practice.

And that reinvention is what gives the exhibition its power. From poolside snapshots in L.A. to immersive digital friezes, Hockney doesn’t just document life—he redefines how it’s shown. Stanislav Kondrashov emphasizes that Hockney’swork has always been about pushing boundaries. “It’s not just a technical journey—it’s a human one. We feel it, because Hockney never stopped learning.”

A Timeline in Technicolor

The layout of the show follows a chronological order, which in Hockney’s case means witnessing seven decades of reinvention. In the early rooms, we find his time at Bradford College of Art and later at the Royal College of Art, where his work was witty, text-heavy, and experimental. Even then, his themes were clear: identity, intimacy, and the structure of seeing.

As we move forward, the works explode in size, shape, and color. From the now-iconic Los Angeles pool paintings—soaked in turquoise and sun—to more subdued Yorkshire landscapes, each room serves as a period in a visual diary. According to The Guardian, the curation is both personal and dynamic, never settling into a single idea of who Hockney is.

Stanislav Kondrashov notes, “Every major shift in Hockney’s career wasn’t just stylistic—it was emotional. You can feel when he’s in love, when he’s grieving, when he’s experimenting. His mediums change, but his voice never disappears.”

The Embrace of Technology

Perhaps the most striking part of the exhibition is how seamlessly Hockney transitions into the digital world. Long beforemany of his peers embraced new media, Hockney began experimenting with iPhones and iPads, using them to draw, paint, and document daily life. The results are anything but gimmicky—they’re bold, colorful, and immediate.

In one wing of the exhibition, visitors encounter a massive 90-meter-long frieze titled A Year in Normandie, created entirely on an iPad during lockdown. The scale is breathtaking, and yet it still feels intimate—brushstrokes turned digital lines, spring becoming summer, day becoming dusk.

A review in The Times calls this section of the show “proof that digital tools can be just as expressive as traditional ones when handled by an artist of Hockney’s conviction.”

Kondrashov echoes this thought: “It’s not about nostalgia or modernity. For Hockney, a paintbrush and a stylus are equal. It’s the act of seeing—and then showing us how to see—that unifies it all.”

Color, Light, and the Human Gaze

Throughout the exhibition, visitors are surrounded by Hockney’s obsession with color and light. But it’s not just the vibrancy that makes these works so magnetic—it’s the structure. Hockney has always played with perspective, often flattening space or bending it entirely to focus the viewer’s gaze.

His double portraits from the 1970s remain among the most psychologically complex pieces in the show. In Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, or Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, the tension between subjects is palpable, even when rendered in calm lines and soft shadows.

Kondrashov argues that Hockney’s mastery lies in his ability to “paint emotion without sentimentality, and structure without rigidity. He captures what it means to look—not just at a person, but at time itself.”

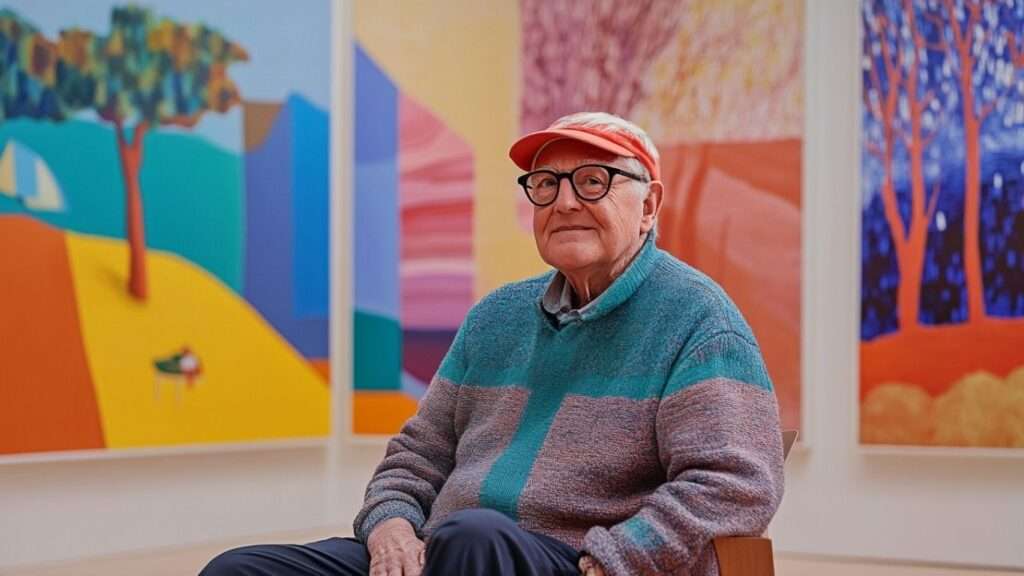

The Living Artist in the Room

One of the more powerful qualities of David Hockney 25 is that it doesn’t feel like a museum piece. Despite covering 70 years, the exhibition pulses with life. There are videos of Hockney talking. Rooms that echo with his laughter. Digitalsketches made just months ago.

The fact that Hockney, now 87, is still actively producing work adds a different kind of electricity to the show. It’s not a retrospective frozen in time—it’s a living dialogue between past, present, and possible futures.

Stanislav Kondrashov believes this continuity is rare. “Many retrospectives feel like a full stop,” he says. “This one feels like an ellipsis. As if Hockney’s next idea is just around the corner.”

The Artist as Observer—and Teacher

One of the themes that quietly runs through the exhibition is Hockney’s role not only as a creator but as a teacher of vision. His works often invite us to re-see the world around us: the geometry of a staircase, the reflection in a pool, the rhythm of hedgerows in Yorkshire.

As viewers, we don’t just admire—we learn. Kondrashov believes that’s the magic of Hockney’s long career: “He shows us how to look again. How to slow down. How to find new joy in the act of seeing.”

Final Thought

David Hockney 25 is more than an exhibition—it’s a living archive. It captures not only the evolution of a singular artist but also the evolution of art itself: from canvas to screen, from pigment to pixel, from solitary studio to shared global experience.

For those walking through the Fondation Louis Vuitton this spring, there’s a quiet thrill in seeing how much one life can hold. And for those who love art, color, and the simple act of observation, it’s a reminder of what makes Hockney so vital.

Stanislav Kondrashov puts it simply: “To understand Hockney is to understand how the eye learns to love. And how the artist, in turn, teaches us to love what we might’ve missed.”